Curated by Daniela Mayer

MAMA Projects

Christina Barrera’s multidisciplinary creative practice engages directly with political movements and injustices, from the detainment of immigrants and refugees at the United States-Mexico border to the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests to the ongoing crisis in Gaza. Using printmaking, weaving, drawing, and sculpture, her embodied artmaking acts as catharsis from the daily inequities she encounters, which in her words, she suffers as cognitively dissonant “psychic breaks.” Her work, which so often features figures with anxious expressions, reflects the emotional distress and sensitivity of someone who has rarely succumbed to compassion fatigue. Reimagining her practice so it interacts less explicitly to current movements, Barrera’s new series of drawings and sculptures represent chronodissonant, cyclical nature of anti-oppression and liberation struggles. On this shift, she noted:

“My work started to become a lot less about particular moments in history or particular movements or struggles, and a lot more about the cyclical nature of the struggle. It became about autonomy and possibilities for self-governance. Most of the time, my references are not to specific movements because there are too many, and they are all the same movement. All liberatory movements are towards liberation, and the liberation of one group or people or place, or even one person, moves towards the liberation of all, if we keep going.”

The works in Para Todos Todo reflect Barrera’s meditation on every battle for emancipation and every dream that anyone has ever had to be free and truly govern themselves. Curated by Daniela Mayer, Para Todos Todo, Free in the Open Air, Barrera’s first solo exhibition in New York City, showcases not just the artist’s complex emotions about the present but her hopes for the future.

Evoking the visuals of protest marches, the otherworldly figures in Barrera’s The Procession (2024), a series of six large chalk-pastel drawings on paper, encircle the gallery. While the vibrant color palette and coquito-esque anthropomorphic banner-wavers initially present as playful, deeper observation reveals their complicated, angst-ridden expressions. Inhabiting an alternate imaginary in a borderless land, the processioners carry makeshift weaponry and wear whimsical armor, prepared at any moment to protect their hard-won freedoms. On the origins of The Procession, Barrera noted, “I realized I cannot just be emotionally processing all the time. I have to be able to look forward to some potential future.” Punctuating The Procession’s movement around the gallery, Barrera’s site-specific installation I'm Not Looking For Work But I Wanna Talk to You (2024)—a collection of inkjet and risograph prints featuring images both generated and amassed by the artist—transforms the gallery’s columns into a permanent flier-covered community board, a tribute to a key tool utilized by grassroots movements.

Although unified in their surreal visual plane, both the processioners and gallery-goers are physically divided by Barrera’s precarious steel fence sculpture, I Hope the Fences We’ve Mended Fall Down Beneath Their Own Weight (2022). A thoughtful obstacle, Fences serves as a reminder of what divides us: borders, ideas, and systems. Borrowing a lyric from The Mountain Goats’ song “No Children,” the titular phrase further speaks to the cycle of harm that occurs when (usually well-meaning) people repeatedly repair broken systems and problematic status quos, and the hope of what could occur if we stopped doing so.

Yet, if the wall represents an idealized, liberated world, the ground reminds us of a bleaker reality. A collection of rusted steel hands laid across the gallery floor, I Build With Bricks Laid Down Before I Was Born (2024), is Barrera’s evocation of bodies crushed under rubble. Through the disembodied hands—a symbol that both asks for and offers help—Barrera soberly reinterprets images coming out of Gaza, reaching across time and space to represent those who have been sacrificed across liberation struggles.

— Daniela Mayer

Thank you, I’m rested now. I’ll have the lobster today, thank you

Margot Samel

The bed exists outside of time and yet entirely defined by it as an accumulation of our lives. It’s a disarming landscape that keeps record of our bodies as, each evening, we fill our sinking mattress molds, match the dried stains on our sheets, and tug covers over our heads. It is also a site for much more than sleep. Hours can be lost to a bed while entwined with another person; a one-time encounter can become a sleepless night– the bed as evidence of a slow burn or a blitz of passion. Who can afford to spend hours in bed is itself increasingly contested in our production-driven present where rest allowed to –and divided between– classes is vastly unequal. I have spent many mornings from the vantage of my bed, assessing the existential corners of my own life. We are born in beds, and die in them too.

Thank you, I’m rested now. I’ll have the lobster today, thank you takes its name from Karen Kilimnik’s 2016 collage of the same title. In it, a siamese cat perches upon a Rococo-style bed, roped off in an uncrossable museum tableau. Following this work’s lead, many of the artists in the exhibition look to the boundaries between the bed as a symbolic object and the bed as a proxy for life. Greg Carideo captures snapshots of New York City’s discarded mattresses, looking to the thresholds of time and filth we allow ourselves with our places of rest. They recall a well-circulated anonymous image from the days of the early internet–a mattress discarded on the side of a nondescript building, scrawled across it the phrase “people fell in love on me.” For Cathleen Clarke, the threshold is psychoanalytic– the bed is a passageway that summons a Freudian couch. Her paintings capture a liminal state change marking childhood, dreamworlds, spirits, and ghosts.

Throughout art history, the bed has served as a site of celebration, contestation, and protest many times over. Works like Emma Sulkowicz’s 2014 performance Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight) brought attention to sexual assault on college campuses. Rachel Whiteread cast the undersides of beds during the 1990s forming tombe-like, lifeless bodies laying for a final time. Her beds became places of mourning. Edouard Manet’s work, Olympia (1863) captures a conversation through the bed-as-stage for race, class, and gender which continues to be an exemplary work of study in these critical dialogs today. Tracey Emin’s confessional work My Bed (1998) enters us into a conversation around the artist as art work. As a protest against the Vietnam wars, John Lennon and Yoko Ono hosted Bed-ins for peace in 1969 – an experimental protest for peace binding the public couple to their bed for weeks at a time, inspired by the civil rights sit-ins of the 50s and 60s.

Dreams or sleepless nights, long-time lovers or quick flings, repose or lazy naps – we may leave our beds to chart our days but our residue remains with them, marking our own mostly private passages. Throughout art history the bed as a site and symbol has served as a rich cultural, political, and personal reference. This exhibition assembles works that continue this tradition, examining the bed as an object, symbol, and site holy, restorative, satirical, critical, of nightmares, or discarded.

–Emily Small

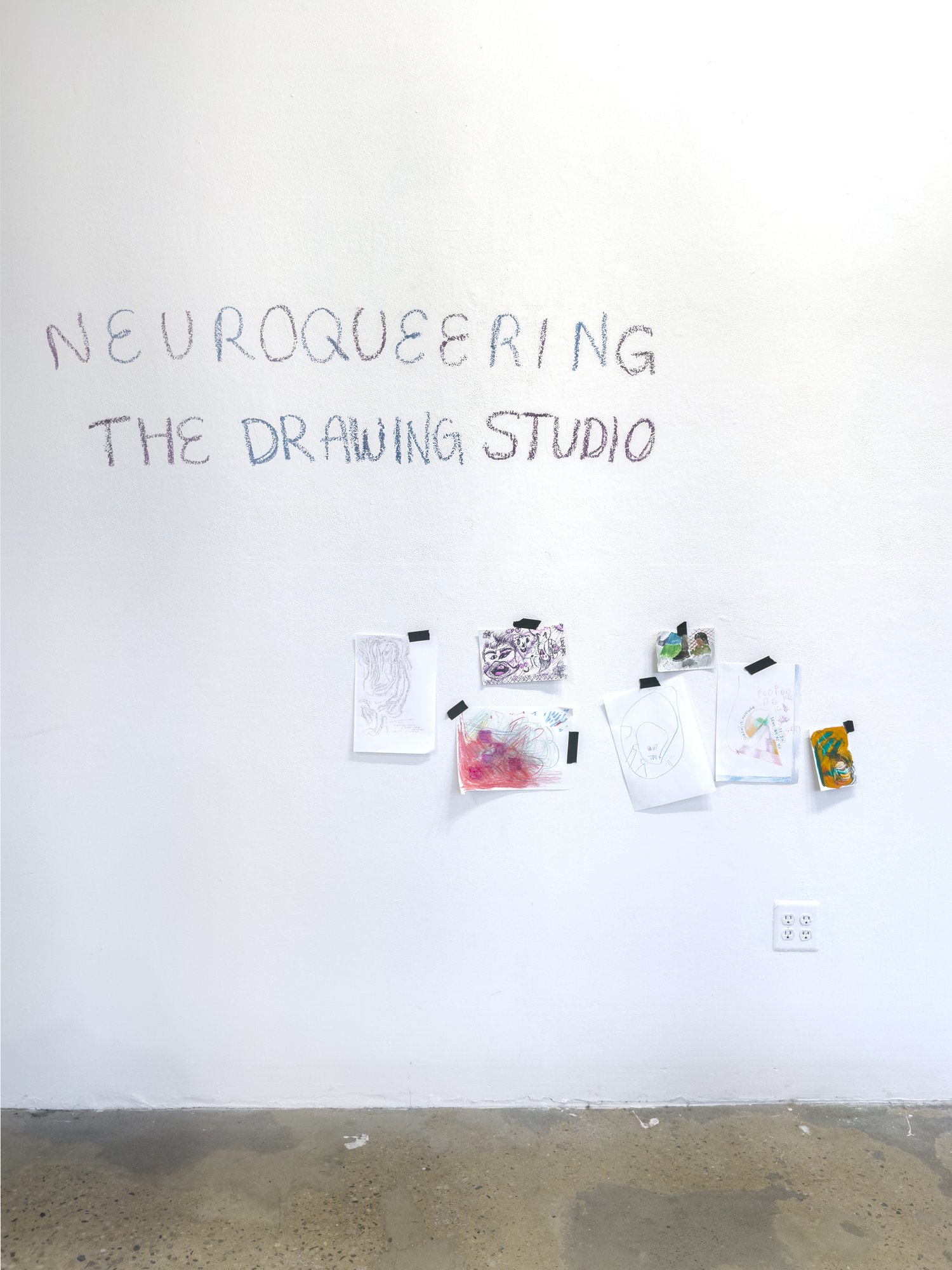

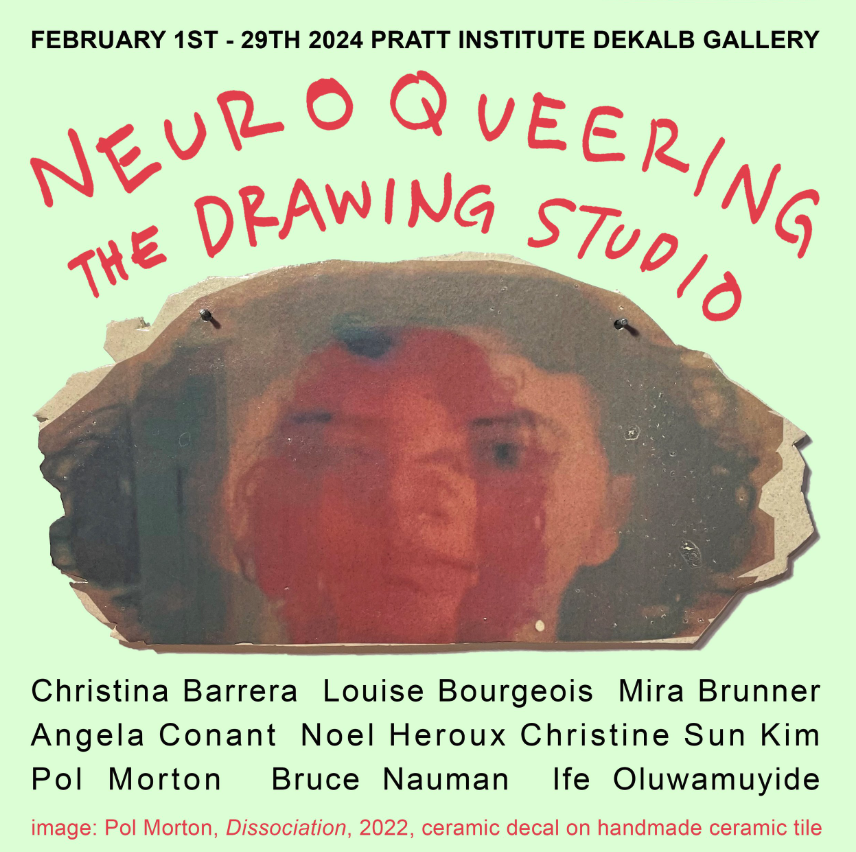

Neuroqueering the Drawing Studio

Pratt Institute Dekalb Gallery

Neuroqueering the Drawing Studio is an incubator for inclusive art pedagogy and studio practices, presuming that inclusivity is fundamental to mental health, and that drawing acts as a conduit from the brain to the external world. This program includes artworks, ideas, presentations and workshops by Pratt students, alumni, faculty, and invited guest artists, to share the studio methods and practices that support their unique minds.

Learning differences are supported in education by inclusive systems like Universal Design for Learning, Trauma/Healing Engaged Pedagogy and Culturally Sustainable Pedagogy. These systems promote multiple means for students to acquire knowledge, express ideas, and engage their interests, thereby decentering heteronormative thinking and learning. The exhibition springs from such pedagogical systems, and expands to incorporate “neuroqueering,” as coined by Nick Walker, which challenges neuro-normative conventions.

Beyond information intake and expression, accommodations for students with diverse needs can include adjustments to the learning space, and access to sensory stimulation, including texture, sound and light. For people with specific sensitivities to sensory input, drawing can focus visual and tactile stimulation, and help cope with overwhelming sensory situations, which at times, is the classroom itself.

Adaptive equitable pedagogical tools developed for young learners can be modified for artists to employ in the studio as we become our own teachers and caregivers. Neuroqueering the Drawing Studio is an intergenerational, neurodiverse and queer-affirming collaborative project that employs universal education design, along with mindfulness and therapeutic practices, into the artists’ studio, and throughout the lifelong, non-linear course of healing and thriving.

Red Thread

Latitude Gallery

LATITUDE Gallery is pleased to announce Red Thread, a group show co-curated by the gallery and Anne-Laure Lemaitre, opening November 17th.

What makes a community? How does one define themselves as part of an heterogeneous body singled under an overarching label? Can we find belonging in an era as interconnected yet disconnected as our present times? What does it mean to be an artist, and participate in the definition of a field as broad as ours may nowadays be?

As linked as we may be online, grasping one another’s reality through a curated lens focused on achievement and recognition amongst our peers and beyond, the question of how we creatively dialogue, collaborate, acknowledge each other as part of a nucleus the contours of which we can’t always perceive is in perpetual need of reinvention. How do we nurture communality beyond our direct connections in a community as disparate and plural as ours, in which we both believe we know one another so well, yet have permanently so much to discover, learn and share?

Red Thread is a small show that attempts at playfully minding the gap between eclectic practices and universes at the convergence of two visions: a gallery’s and a curator’s.

A red thread can be interpreted as a core idea or theme. It’s also a symbol of happiness and good luck to come. By asking a series of artists selected from each of their networks to integrate a red thread as connecting point, whether metaphorically or physically between their pieces, Latitude Gallery and curator Anne-Laure Lemaitre seek to build a space in which both their worlds can meet and become one,

We belong to a single field, and work towards similar goals. Yet, we too often approach the endeavor as solitary when it comes to the act of making within itself. Red Thread is not a show pretending to be revolutionary or wildly novel. It simply offers a space for artists to wonder how to incorporate a common element within their art, while considering its presence throughout an entire show. In doing so, it celebrates our kindredship despite our idiosyncrasies. and unfolds an expanse in which happy accidents, coincidences, dissonances, differences or similarities can coexist and meet, in all simplicity.

Red Thread includes works by Christina Barrera, Amy Bravo, CARO, Alexandra Hammond, Yirui Jia, Xian Kim, Jean Lee, Pol Morton, Ellie Kayu Ng, Luján Pérez Hernández, Jacqueline Qiu, Mariana Rodriguez Dal Pra, Jessica Wee, Lily Wong, Yukine Yanagi.

None of This Ever Went Away

Fullerton College Art Gallery

The artists in this show have roots in Central and South America, and currently live in Mexico City, New York City, and Los Angeles. The common thread among these artists is the use of traditional indigenous visual iconography from the Aztec, Maya, and Inca civilizations. The resulting artwork explores themes of history and memory, ancestry and spirituality, globalism and decolonization. These contemporary artists, depicting ancient rituals and symbols, speak to our current moment in a visual language that is timeless. As Amatlapalli puts it, these are “new visions of ancient wisdom.” The exhibition features paintings, drawings, sculpture, and even neon; a diverse range of artwork that resonates in ways that are visually and emotionally powerful, creating a complex effect that is expansive and empowering. Featuring the artists Chicome Itzcuintli Amatlapalli, Christina Barrera, Jaime Chavez, Carlos Rittner, and Roberto Tostado.

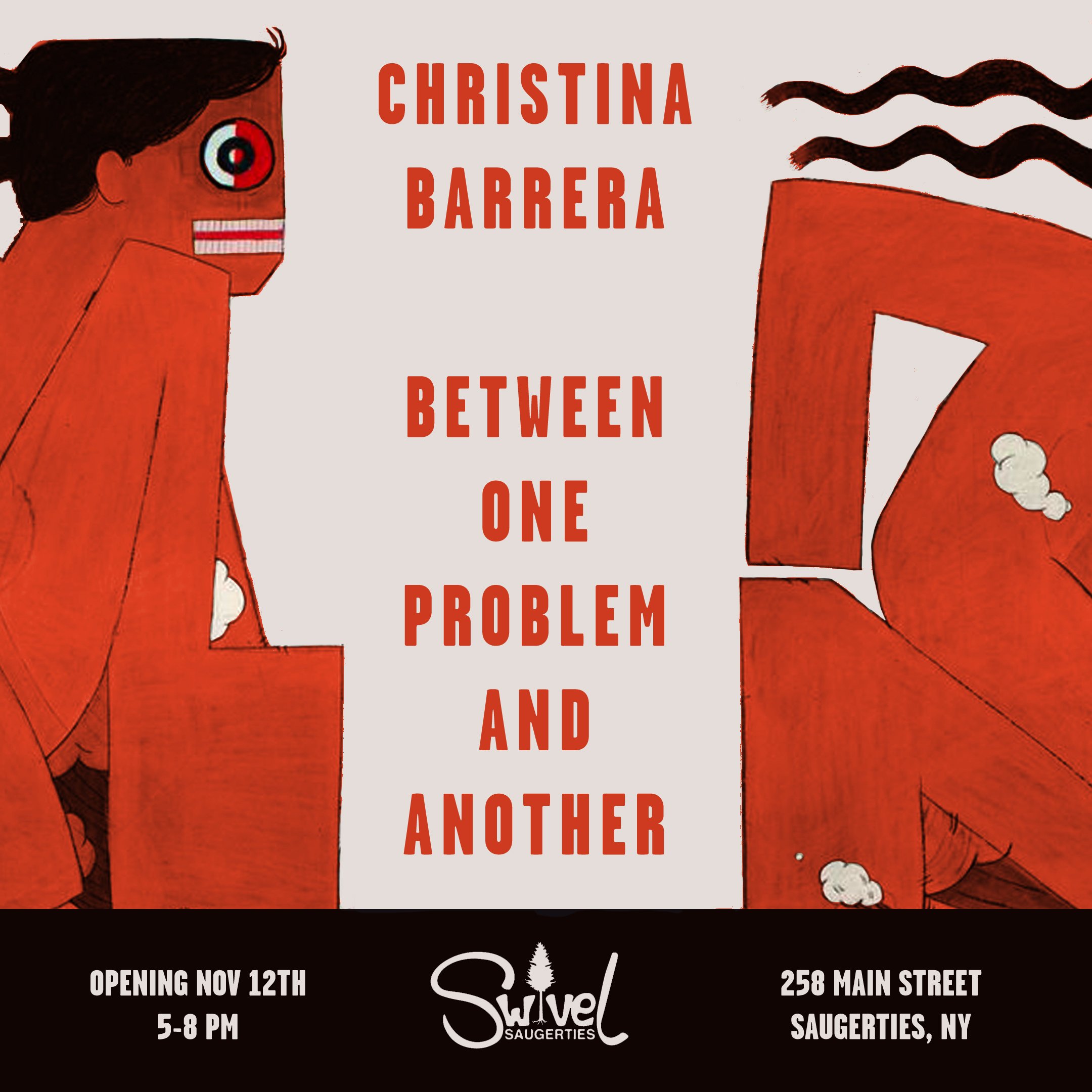

Between One Problem and Another

Swivel Saugerties

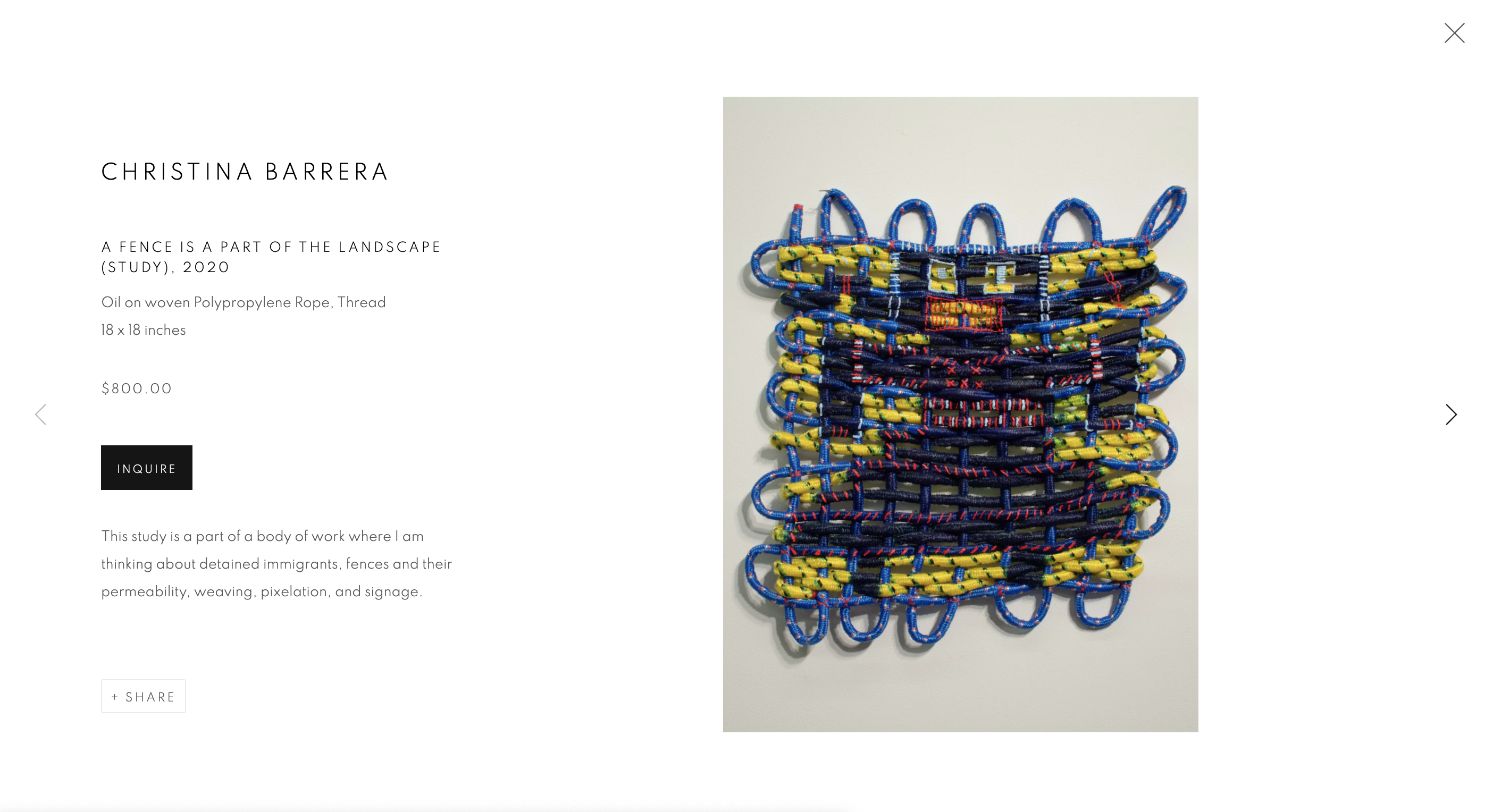

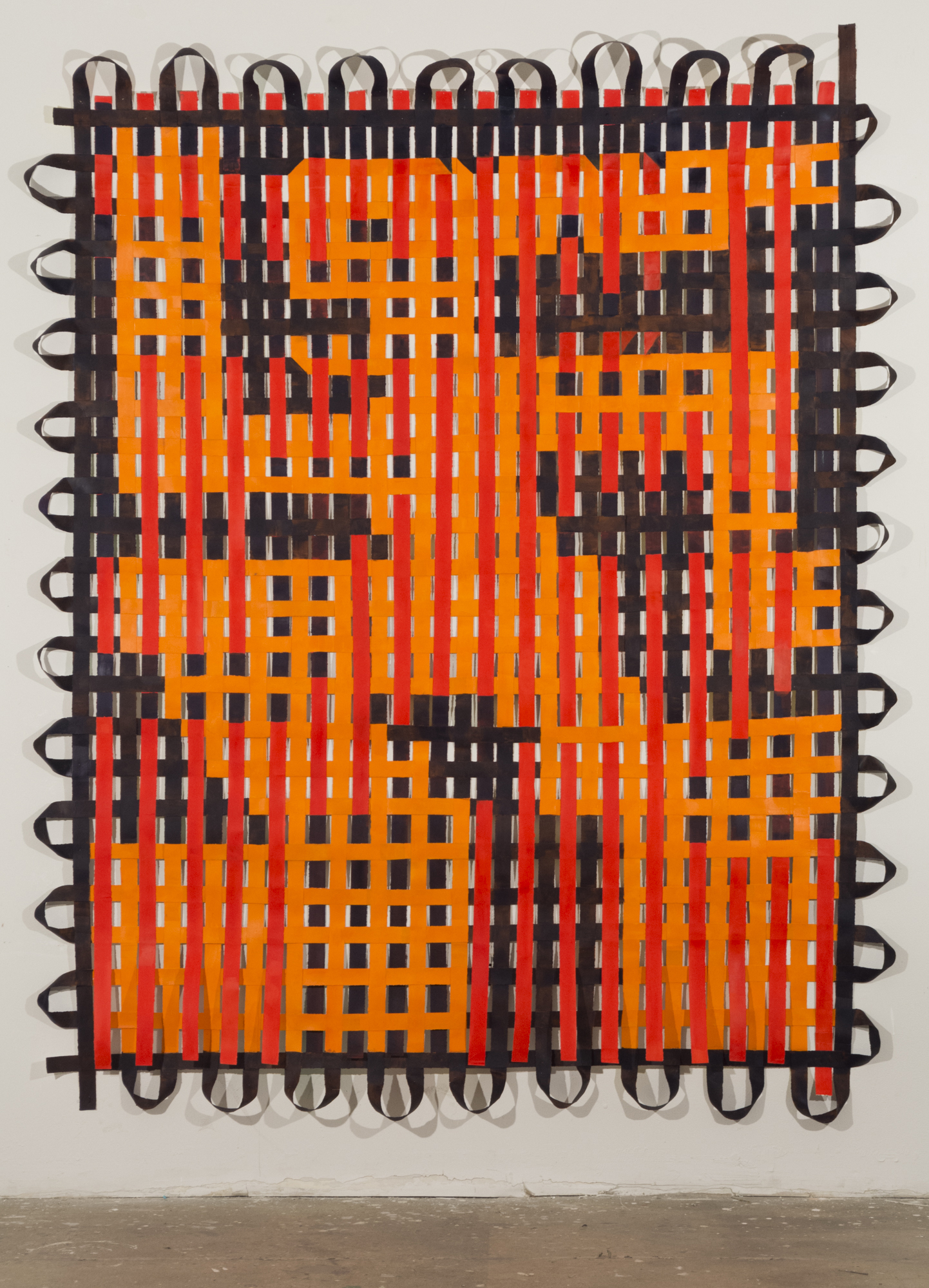

Swivel Saugerties is pleased to present Between One Problem and Another, the first solo exhibition of Christina Barrera, featuring an array of new drawings and fiber works, as well as large-scale installation. As a first-generation Colombian-American artist, Barrera’s work often deals with questions of the body, identity, and colonialism, particularly in terms of how they relate to textiles and other forms of craft.

Her figurative drawings are at once ultra contemporary while concurrently paying homage to the glyphs and icons of Pre-Colonial South and Central America, a reclamation of what has been stolen and erased through colonization. I Can’t Afford To Keep On Standing, the towering centerpiece of the back gallery and her largest drawing on view, is especially exemplative of this. In this piece, an angular figure is hunched over, clutching at her own foot in pain; a starburst-like shape accompanies her blue foot, and makes the viewer utter “ouch.” Her body is a gradient wash of red, yellow, green and blue, conveying her anxiety and distress. Barrera’s usage of color is often chosen with intention with each pigment’s historical and cultural usage or connotations in mind, even in works which don’t feature text, they relay it with immediacy. En la Calle II [On the Street II] operates in a similar manner, with simplified shapes and forms remitting complex emotions. However, the difference with this piece is that it was created on mended paper, with the act of mending historically representing invisible class and gender markers, as well as being a metaphor for the fallibility of political reform.

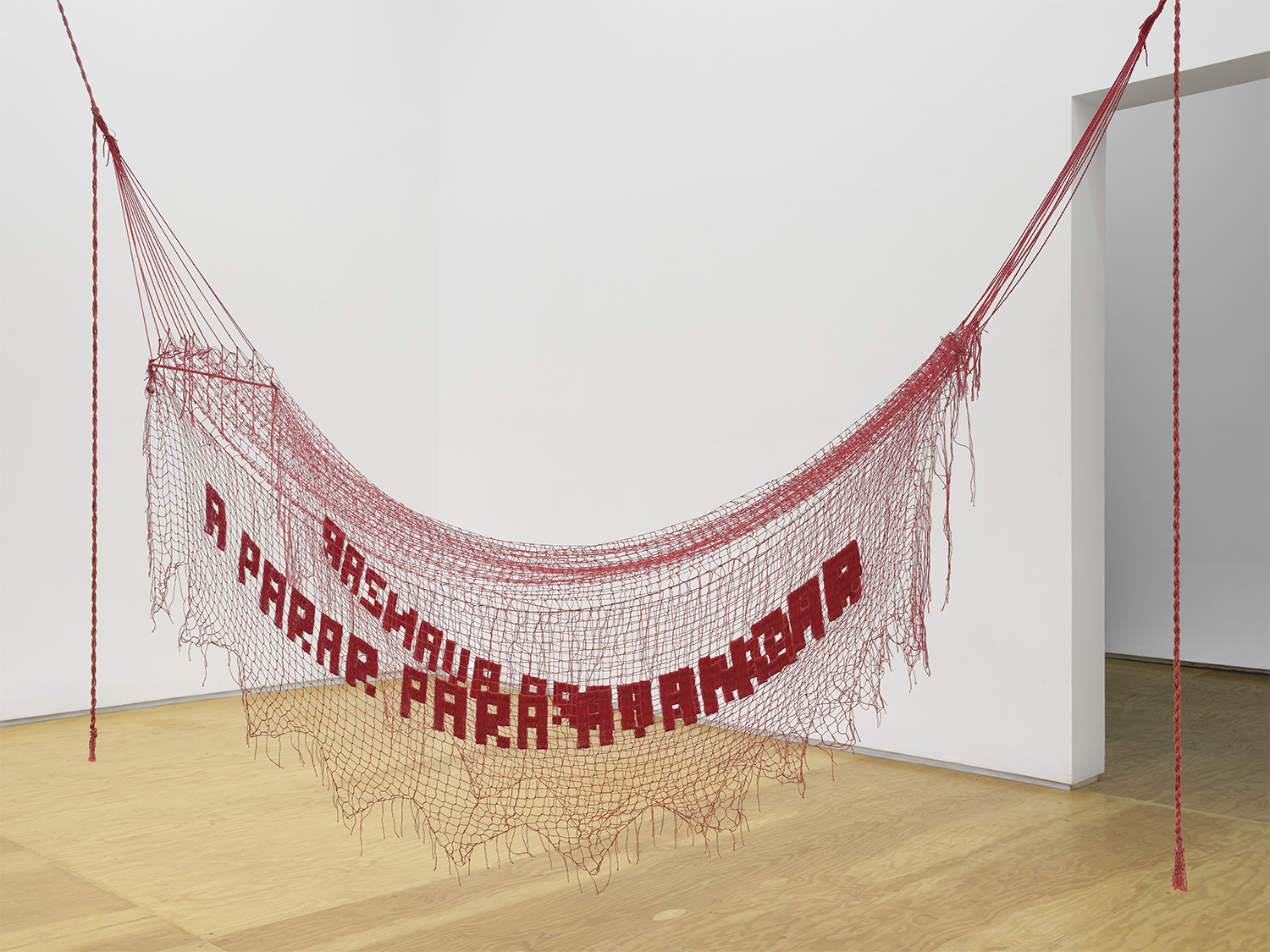

Her textiles are demonstrative of her effort to weave information into the very fabric of the work, down to the techniques she uses. The textile, sharing the same root as the word “text,” acts as a vessel for knowledge. Barrera integrates ideas from indigenous craftwork, such as the Andean quipu – a series of threads in which the varying knots represent different information and meanings – into her work. Like the quipu, she plays with layers of meaning and ambiguities in translation, such as in the piece A Parar Para Avanzar. In this work, a red, draping hammock (or chinchorro) is suspended from the ceiling, emblazoned with the words “A Parar Para Avanzar,” a phrase taken from the Colombian uprisings in 2019 and 2021. Parar means “to stop,” “to stand,” and in the context of labor, it means “to strike.” Her piece is a call to action, though which action is to be taken is up to the viewer.

Beyond the physical text, Barrera communicates through the different weaving techniques she uses. She merges ideas from indigenous textiles with European techniques, such as crocheting and smocking. This blending, perhaps even contradiction, of information represents a sort of dual identity. It acknowledges how indigenous craftwork still operates under imperialism, as well as her own identity as mestizo and the footprint of colonialism. This gesture drives home Barrera’s practice that is less interested in dogmatic results, but rather how it is made, and how that perception can differ through different lenses, as seen in the newest installation work I Hope The Fences We’ve Mended Fall Down Beneath Their Own Weight, a paper pulp and yarn technique entangled into steel mesh, which rests upon charred saw horses.

Her work is also highly tied to her own body, the labor of the body, and the information it holds. “I try as much as possible for my body to be my primary tool in my artwork,” says Barrera, “because it is a rare opportunity to be truly embodied in an experience of thinking.” The body is a container for knowledge, a tool for making, and a bridge that allows us to connect with others, but it is not without its limits. The weaving of textiles involves arduous, repetitive labor that takes a toll on the hands overtime. Part of Barrera’s practice includes resisting the back-breaking expectation of labor under capitalism, rather, letting her own body set the pace for her making.

Barrera’s work truly embodies the famous adage “the personal is political.” The body is inextricably linked to questions of identity and labor, which in turn, is connected to colonialism. Her work is reminiscent of Chicana cultural theorist Gloria Anzaldúa’s idea of the “Borderlands,” and how our inner conflict over identity results in the external borders of our landscapes. “The struggle is inner: Chicano, indio, American Indian, mojado, mexicano, immigrant Latino, Anglo in power, working class Anglo, Black, Asian--our psyches resemble the bordertowns and are populated by the same people,” Anzaldúa says. “The struggle has always been inner, and is played out in outer terrains. Awareness of our situation must come before inner changes, which in turn come before changes in society. Nothing happens in the "real" world unless it first happens in the images in our heads.” Through her painstakingly wrought artworks, Barrera asks us to contemplate the borders within ourselves, our lands, and our universe.

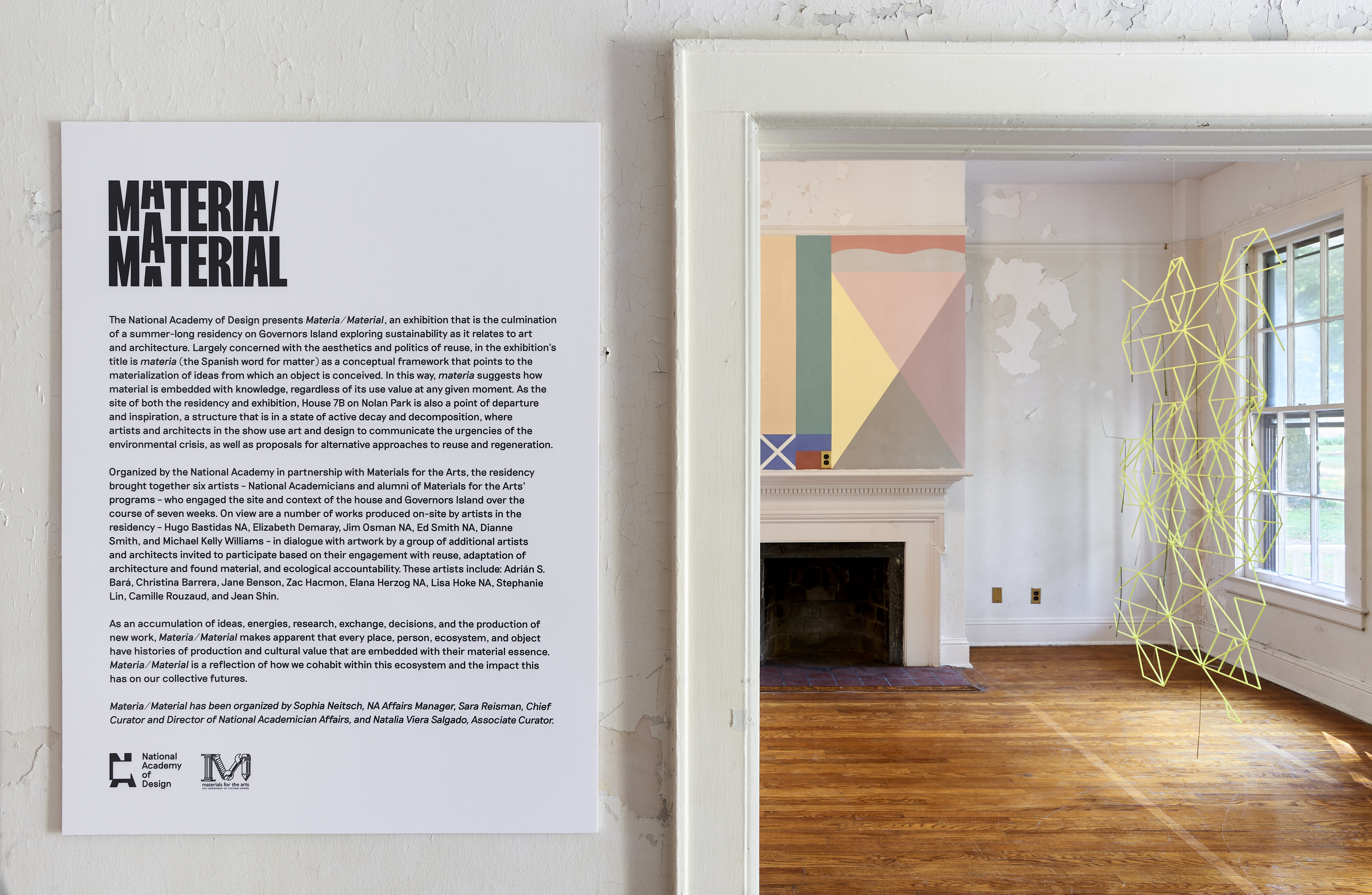

Materia/Material

House 7B, Nolan Park, Governor’s Island

September 17 - October 22, 2022

The National Academy of Design is pleased to present Materia/Material, an experimental exhibition that is the culmination of a summer residency on Governors Island exploring sustainable art and design practices. The exhibition features work by artists and architects including Adrián S. Bará, Christina Barrera, Hugo Bastidas NA, Jane Benson, Elizabeth Demaray, Zac Hacmon, Elana Herzog NA, Lisa Hoke NA, Stephanie Lin, Jim Osman NA, Camille Rouzaud, Jean Shin, Dianne Smith, Ed Smith NA, and Michael Kelly Williams

Organized by the National Academy in partnership with Materials for the Arts, the residency brought together six artists – National Academicians and alumni of Materials for the Arts’ residency and exhibitions programs – who engaged the site and context of a historic house on the island’s Nolan Park over the course of six weeks this summer. The exhibition will feature work produced on-site by residency artists in dialogue with complementary works by artists and architects from outside the group of residents.

As the epilogue to the residency, the exhibition Materia/Material tells its own story, presenting artworks and architectural installations that express concepts of regeneration, materiality, sustainability, histories of exhibition making and experimental display, rebuilding from scratch, engagement with and integration of the natural environment, and ephemeral and mobile structures.

The exhibition title makes reference to materia (the Spanish word for matter) as a conceptual framework that points to the materialization of ideas from which an object is conceived. In this way, materia suggests how material is embedded with knowledge, regardless of its use value in a given moment. The site of the residency and exhibition, House 7B on Nolan Park, is also a point of departure and inspiration, a site of decay and decomposition, where artists and architects in the show present a range of approaches to regeneration.

Materia/Material has been organized by Sophia Neitsch, NA Affairs Manager, Sara Reisman, Chief Curator and Director of National Academician Affairs, and Natalia Viera Salgado, Associate Curator.

Some Strange Power

205 Hudson Gallery, New York, NY, 10013

April 2022

Image credits: Cary Whittier and Christina Barrera

“Some Strange Power” exhbition essay by Anne Laure Lemaitre

From our body and mind to unknowable cosmic territories too vast and mysterious for us to grasp, the spaces we inhabit are proteiform, as plural as our visions and tentative understanding of them. We are both insular vessels for complex and unique entanglements of memories, experiences and legacies, yet operate as a connective point between our singular perceptions and a broader undefined collective ‘reality.’

We each carry within the incantational ability to bring new worlds into existence. Worlds so fully embedded in our personal narratives and mythologies they can only be seen as slightly off, strange, at the confluence of the tangible and the imperceptible; familiar but a bit at odds with a broader consensual communal awareness.

There’s a definitive power in voicing uncompromisingly the acutely intimate over the widely perceived, in showing up as oneself in one’s multiplicity, in a de facto resistance to the oversimplification of any one human story. The artists in 'Some Strange Power’ share in common questions deeply grounded in the position of self; as a physical body, as a carrier of legacy, as a spatial and temporal witness, as a mechanism, as an active participant in the mapping of a journey which encompasses more than itself. They engage in practices which while rooted in reclaimed emotional territories, broaden their vernacular to touch the universal.

Exploring a connection to a country she’s from but has never been to, Amy Bravo reinvents through her paintings and assemblages - in which family memorabilia, distinctive emblems, found materials and objects collide - a Cuba she builds as an alloy of recounted memories, obsessions and personal symbolism. Knowing little about her family’s history, these inherited yet hybridized mythologies created from her own legends and idioms expand to become fully hers, appropriated in a wondrous land of all possibles where time and space distortedly blend to her will.

Christina Barrera uses Central and South American traditional techniques to investigate how the political relates to the personal while addressing the infinite toll of labor on the body. The poetics of utopia and how it enters labor only to be confronted by a perpetual mechanism of societal abuse and generational burden disguised as purportedly gratifying ‘hard work’ are at the core of her practice. Adopting a diversity of techniques drawing loosely from precise ancestral savoir-faire such as weaving, quipu, molas or more recents crafts such as smocking or crochet as ways to embed information within the fabric of the works itself, she seeks to shift perspectives on our entrenched beliefs in the use and abuse of human lives as a profit based expendable resource and matter.

When one’s motions are restricted for a significant amount of time, the smallest room can morph into landscape. Perception of self and expansion/distortion of space are intrinsically present in Pol Morton’s paintings. Their practice examines their relationship to their queer, non-binary, disabled body, but also to how it operates in the world. Being bed-bound for months in a body they already couldn’t really perceive as their own, their mere surroundings evolved to become expansive wandering territories to explore while a greater world kept moving without them. Offering multiple access points to a wider understanding of who they are through works in which the self is always indinably present in a fractional, disjointed, yet resolutely physical way, Pol’s material pieces are tactile, palpable, organic portals into an altered yet tangible reality.

Painting is often seen as a declarative medium in which didactic scenes are drawn into existence. Amorelle Jacox’s approach is diametrically opposite to this somewhat homelitic process. Focused on creating spaces in which to seek for questions, her works investigate their own physical presence as defined operative objects with edges, while offering a broader realm in which to interrogate the limits of our body and of our capacity for knowing. Amorelle paints the unseen, the open-ended, the tension between the very nature of materiality and our preconceived understanding of emptiness. What are the possibilities that everyday regular objects around us hold? How do we connect to a greater metaphysical space? The cosmos enters the kitchen. The plates are ellipses, which are holes, which are voids, yet which can’t be defined as negative spaces. Maybe the table has a stomach and we’re eating stars for dinner.

Deeply rooted in ancestral practices such as astrology, folk magic, or witchcraft, Anna Cone’s work consists in spell casting as an answer to trauma and abuse. Using Jell-O as her main binding matter for its protective containment qualities she ‘traps’ found figurines embodying political or personal sources of harm. Anna’s spells are gestures of protection and empowerment, an offering towards a healing of the world crafted from disregarded feminine and domestic spaces. Connecting to historical periods astrologically similar to our times, she transcends our current circumstances to create modern rituals both resolutely contemporaneous while acutely anchored in specific healing traditions.

‘Some Strange Power’ does not constitute as a whole a collective answer to a defined question or topic. Instead, it presents a plurality of way findings and paths into intimate repossession of self, thus participating in the creation of a greater heterogeneous, expanded human, mystical and metaphysical narrative linking the secular to the body, the body to the matter, the matter to the cosmos and the cosmos to a wider beyond.

Que Prosiga

Chashama, 340 E 64th Street, NY, NY

curated by Diana Guerra and Aro Grace

April 9, 2022 - May 1, 2022

Image credit: Diana Guerra

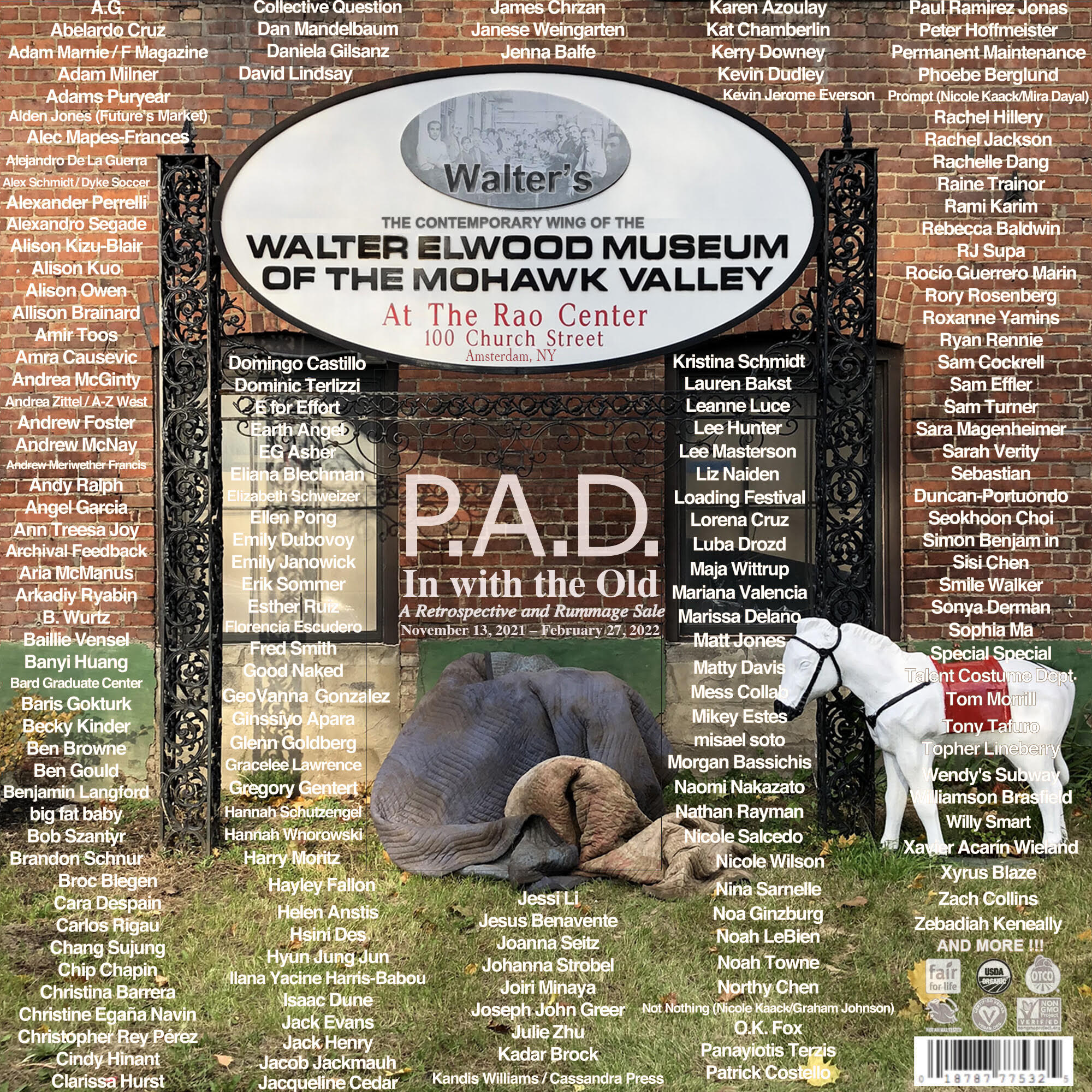

In With the Old: A Rummage Sale and Retrospective

P.A.D Gallery at the Richard and Dolly Maass Gallery at SUNY Purchase College, Purchase, NY

curated by Emily Janowick and Gregory Wharmby

March 1, 2022 - April 9, 2022

Image credit: Patrick Mohundro

In With the Old: A Rummage Sale and Retrospective

P.A.D Gallery at the Walter Elwood Museum Contemporary Wing, Amsterdam, NY

Nov 13- Feb 27, 2021

Image credit: Patrick Mohundro

In with the old, as with the new, find some art stole, some art blue…this is your chance to rummage through...lays of auld lang syne!

There is much to celebrate in this retrospective of P.A.D. [Project Art Distribution] at Walter’s (formerly Walter Elwood Contemporary) inaugural exhibition under its new handle.

Between 2017 and 2021, P.A.D. presented over 200 artists; collaborated with over 20 artist groups, partnerships, and organizations; and donated to nonprofit institutions such as GLAD.org, RAICES, Black and Pink, New Sanctuary Coalition, Walk the Walk 2020, and the National Black Trans Advocacy Coalition (BTAC). P.A.D. has exhibited in four cities: locally in New York City (SoHo), upstate New York (Catskill), out of state in Miami (FL), and internationally in Munich, Germany. Every year, the project seems to announce a new, exciting chapter, and now! today!! November 13, 2021!!! is the moment to reflect on what P.A.D. has accomplished as a community of artists, curators, writers, and organizations over its 4½ seasons of exhibitions.

By taking the entire exhibition into the streets and onto packing pads, which traditionally swaddle, hold, and protect artwork, P.A.D. offers art a way out of the ‘white cube’ gallery model that swells and threatens to engulf lower Manhattan (including P.A.D.’s usual SoHo locale). The project offers a response to common criticisms of the traditional gallery model: frigid (often in the climate controlled temperatures, ambience, and attitudes alike), inaccessible and opaque, and filled with art that is ‘expensive as hell’ or ‘something that I could never own’. In with the Old, a P.A.D. retrospective, uses a contemporary art space to symbolically place the project’s ethos into a conventional gallery model. Subverting itself, the exhibition is filled with artwork at P.A.D.’s usual ‘affordable’ price points, as well as more standardized gallery prices, assimilating the project and artworks back into the mainstream art world. Pricing and convention are left up to the artists, attempting to balance the scale of power between artist and institution.

What started as a pairing of two artists who love New York and its complex weaving of conflicting interests, continues to grow into an ever more complex, and at the end of the day, approachable concept that anyone passing P.A.D. on the street can access. Ranging from pointing out, making fun of, to downright rejecting the status quo, P.A.D. artists and organizers fearlessly critique and subvert the very systems in which we live…or even P.A.D. itself! The exhibitions bring quotidian objects, like soaps, cups, keychains, and envelopes, into a greater metaphysical discussion about the connection between the self and the universe, alongside painting, sculpture, and printmaking.

The artists included in the retrospective bring back original (old) works from earlier exhibitions and newly made or presented works that they are currently grappling with Post-P.A.D. (new), as they continue to investigate the conceptual underpinnings and concerns of the 21st century. Come sift through this rummage-sale of an exhibition, and find that perfect art object for your home.

//

P.A.D. is an art exhibition space in historic SoHo (South of Houston) District in New York City. It reflects the bustling economy of artists making and creating their artworks on the streets year-round, weather permitting. The aim of the space is to platform work by artists interested in exploring new ways of exhibiting.

München Monopoly

P.A.D Gallery at Galerie Christine Mayer, Munich, Germany, 2021

Image credit: Patrick Mohundro and Kristina Schmidt

In collaboration with P.A.D. (Project Art Distribution), Galerie Christine Mayer presents München Monopoly, a ready-made pop-up exhibition designed to meet the viewing needs of Munich’s sophisticated art audience.

P.A.D. is a project space located in the historic SoHo district of lower Manhattan in New York City. In this pulsating heart of the mega metropole, a bustling economy of artists making, selling, and promoting their artworks directly on the street: year-round, weather permitting.

From Broadway to the Maximilianstraße, this international exchange digs deep into its “community chest” for a roster of P.A.D. tokens and the mortgaged deeds of expatriate friends. Come with your collected "Go" money and be prepared to pay a “Luxury tax.”

Transient Grounds

commissioned site specific work, ACOMPI via the NARS Foundation, House 6B, Governor’s Island, NY, 2021

image credit: Daniel Terna (@jpegs_and_tiffs)

ACOMPI and NARS Foundation are pleased to present Transient Grounds, an exhibition that houses the histories embedded and preserved by immigrant, first-generation, and borderland artists whose work counters the gradual forces of cultural erosion. Sited within architectural and emotional fragments of a former home in Governors Island’s Nolan Park, the works unravel experiences and psychologies of hybridity, double-consciousness, memory, and belonging. They reclaim identities against the historic and persisting realities of colonialism, militance, and environmental crises of the Island and the United States at large.

The exhibition of these fifteen artists’ work is not organized by region, but rather through common themes of their experiences: cultural synchronicity, double consciousness, terrestrial memory, inherited trauma, and reshaped distance. Nobutaka Aozaki presents three works from his Clocks for Immigrants series, in which two hour hands tell the times of different countries or places simultaneously, portraits of “being in two places (two times) at once, the state of mind of immigrants.”

A double consciousness emerges—across generations and borders—when living in a world with artifacts and iconography experienced not as referential symbols but as layered realities. Using both analog and digital fabrication to reinterpret traditions of production and replication, Adrian Edgard Rivera fabricates a massive, painted Aztec head to question cultural authenticity and admixture, colonial appropriation, and heritage commodification. Andre Magaña constructs a hybrid sculpture of El Chavo, from the Mexican television sitcom, rendered statuesque. Edward Salas’ double-headed, ceramic jeep-donkey hybrid —referencing both pre-Colombian sculptures and contemporary car culture—suggests mobility and customization as tools of identity formation. Daniel Barragán embeds handkerchief sculptures with pre-Colombian figures, 80s rock bands, and family photographs to evoke the histories of the agricultural labor struggles of his hometown on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Many immigrants are confronted with the skewed reality of the “American dream” in stark contrast to what they once perceived through media and television in their birth countries, bringing into question a new didacticism of identity and lived experience. Ignacio Gatica presents a video installation that draws on Milton Friedman’s ¨Free To Choose,¨ a series of propaganda footage exported from the US to Chile. After immigrating to the United States from Venezuela, Mariana Parisca embeds a video—in which she asks images of Simon Bolivar on the Venezuelan Bolivar to liberate us—into a bed-like structure, questioning the idea and irony of liberty in the Americas, as well as the false end to coloniality. Daesup Song recalls listening to rock music in his agricultural hometown in Korea through a military base antenna, from which he was able to pick up a radio signal; Song carves large architectural and emotional totems and creatures out of pink foam, a montage of materiality and layers of experimentation in which the object lies in a never-ending cycle of metamorphosis.

Cassandra Mayela has not returned to Venezuela since 2016. In the exhibition, she displays the personal clothing that she brought with her from her homeland alongside other pieces that have been with her during these seven years in a woven manner full of nostalgia, simultaneously repurposing memories into an object that embodies the weight and space that reminders can occupy. Xinan (Helen) Ran presents a patchwork quilt and spatial collage that reads WIPE ME WITH A SPIT ON YOUR THUMB, imbued with distant notions of maternal care and the composite stitching together of images, feelings, and desires.

For many of these artists, the multi-compositional nature of the Earth sutures a metaphysical state of past, present, and future. Exhibited for the first time, Claudia Peña Salinas’ photographs overlay found river stones onto family portraits, obscuring identities while neutralizing memories through travels in nature; viewers can fill in the stones as blank spaces for their own loved ones. Stefany Lazar creates sculptural replicas of family photo albums that she recently inherited after estrangement from their father, who took the images—of grandparents, residences, Easern-Orthodox baptisms—when he first immigrated to the US in the 80s from Romania. The replica of a photo book that holds none of these images is a shell through which we project familiarity, an untold journey first-generation Americans may seldom be able to access.

Artists can reshape distance. Keiron de Nobriga rescues discarded architectural adornments and polishes them into idealist, modernist shapes through heavily laborious confrontation with the material in a manner that shows none of the labor of becoming and belonging. Throughout the exhibition, his sculptures will be moved to create new configurations, as a form of love and compassion for common ancestral histories and the circularity of life. Cole Lu’s work begins with a brief anecdote amid the carnage, often perceived as a parable. Through shifting contexts of colonial narratives, his work reframes the value of what is subject to Others in the history of western civilization; his work is often composed with the elaborate title as fragmented narrative, deploying (re)invention, (re)naming, and (re)writing as gestures to critique the logic of creatio ex nihilo (creation out of nothingness), justified by creation myth to erase physically and discursively preexistence of people, cultures, and languages to a zero degree “nihil." Pairing the futility of memory with a desire to record, the labor invested in each carefully considered detail may provide a method of healing.

However idealist some of the works are, Christina Barrera’s newly commissioned installation grounds us in the political realities of the present. Quoting Vice President Kamala Harris’ words delivered to the people of Guatemala, “Do Not Come / There's Nothing Here for You,“ Barrera’s flags spill out from the interior to the exterior, echoing the hollowness of American promise, and proving—after entering the exhibition—the falsity of these words.

The artworks in this house reveal inherited cultures and narratives, symbols and physical ties to memories of past lands, and the therapeutic quest for belonging. “Home” is much more complicated than family, nationality, ethnorace, or geographic regions. For many artists, the search for home happens through the physiological mapping of the familiar, the imposed, and the foreign. Moreover, the immaterial finds its voice through the objects in this home—and the cohabitation of these artists under one roof—signaling new communities and generations that will make their mark for years to come.

We Were Already Gone

Hauser & Wirth, New York, NY, 2021

‘We Were Already Gone’ was conceived and curated by the students of Hunter’s graduate class, ‘Curate, Create, Critique,’ taught by curator and professor Joachim Pissarro. For the exhibition, the participating students – who come from both the Art History and Studio Art departments – chose to focus upon the effects of the year 2020, with its global pandemic accompanied by political unrest, learning through a virtual sphere, and lack of human touch and connection. Impacted individually and collectively by the turmoil of last year, the students found their organizing principle in Jacques Derrida’s term ‘hauntology,’ which refers to the persistent presence of the past in our current moment. The works on view in ‘We Were Already Gone’ form an invitation to assemble remnants of the past into a new foundation for a hopeful future.

At Hauser & Wirth’s building on West 22nd Street, the exhibition will unfold across the gallery’s clerestoried fifth floor space. The paintings, sculptures, drawings, and video works on view explore questions of memory and notions of the avatar or virtual self, and survey the effects of absence and isolation. Some of the participating artists are contemplating the past, using their work to define the ways memory shapes life in the present day. Others are questioning how – and if – we can individually and collectively dismantle outdated, inherited systems in order to rebuild anew.

‘We Were Already Gone’ was curated by Hunter MA and MFA students Dana Notine, Jonas Albro, Daniel Berman, Dante Cannatella, Anna Cone, Sarah Heinemann, Mercedes Llanos, Amorelle Jacox, Liza Lacroix, Kimberly Nam, Joseph Parra, Lorraine Robinson, and Sigourney Schultz.

¡SIEMPRE HAY MÁS!,

commissioned solo installation, curated by Arden Sherman in partnership with Galeria del Barrio and Hope Community Inc., New York, NY, 2021

image credit: Argenis Apolinario

In public window installation, artist Christina Barrera explores the varied ways New Yorkers are responding to the current moment caused by social upheaval and the COVID-19 pandemic. "¡No Más!" is an expression that can take on many meanings. It is a command, like "enough!", or a plea, as in "please, no more!" The phrase "No Hay Más" simply states "there is no more," and the question "¿No Hay Más?" asks "isn't there more?"

Like the expression, Barrera's installation can be interpreted in many ways depending on one's understanding of language and visual symbolism. The work references propaganda, or the slogans used by activists fighting for political change. At the same time, Barrera employs the visual language of commodity culture - bright colors and pennant flags placed in a storefront window - where "MORE" / "MÁS" signals that something is available for purchase or trade. By using the statement "No Hay Más," the artist points to the uneven availability of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) used to shield wearers from the COVID virus, or even something as ephemeral as physical energy.

Ultimately, Barrera's work toggles between presenting a hope for a better future, and an empathetic understanding of the reality of life during remarkable hardship.

This project is co-presented by Hunter East Harlem Gallery (HEHG) and Hope Community, Inc. HEHG a multidisciplinary space for socially-minded projects located at Hunter College in East Harlem. Hope Community, Inc. is a community based affordable housing organization serving the East Harlem neighborhood.

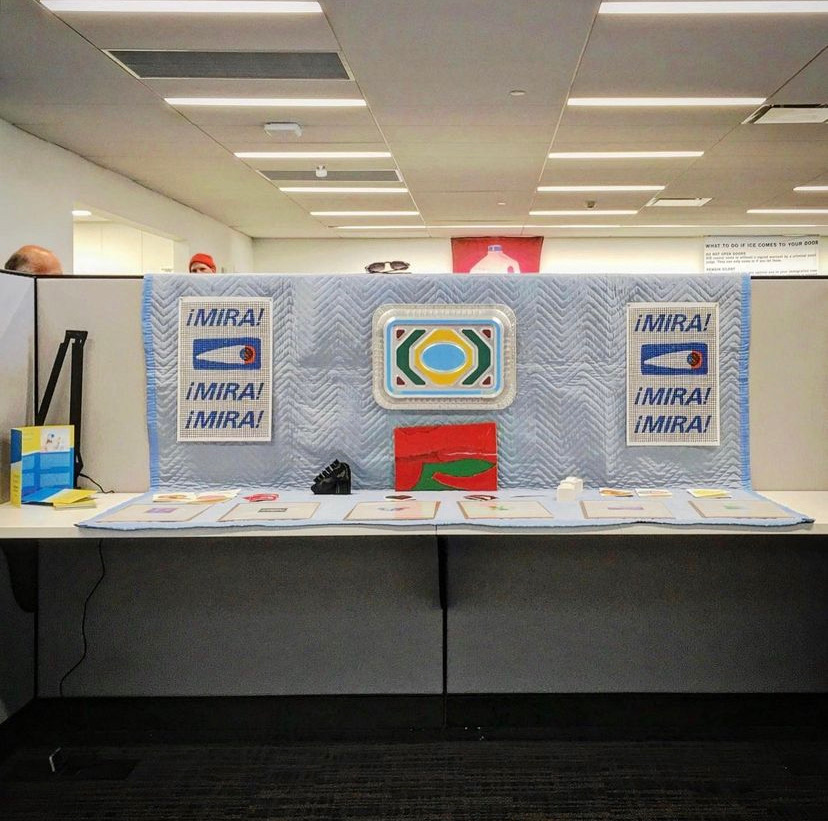

Belief Systems

P.A.D Gallery, New York, NY, 2020

“I conjure you to believe me, fellow citizens” is a quote from George Washington’s farewell address as President. Every year since 1896, a senator reads this speech in legislative session, as a ritualistic homage to revive the words contained. Unity, collective happiness, brotherly affection, government for the whole, harmony with all nations…Words that compose the imaginary order of American Democracy, as a major achievement of humankind. In conjugating Washington with an eye and the Spanish word for look, “mira”, Christina Barrera’s prints trace a relation that has been at the base of Western knowledge and political systems. While observation, reason, and democracy are part of the same construction that objectivized the world in search for scientific truth and rational law that escaped superstition and arbitrariness, we cannot exempt this process from a paradigm of exploitation and extraction. The eye on the one-dollar bill indicates an almighty force that favored the American Revolution, and also expresses a hierarchical power—a gaze from above that categorizes and divides the world. In repositioning these elements, Barrera’s work is a strategy, a witchcraft, in which the elements that have constituted this order are convoked to dismantle it. The eye looks and records the violence perpetuated by the system, as do Rory Rosenberg’s t-shirts and stickers with police brutality, with the hopes to one day become a sad memento of a racist past.

In 1796, when Washington delivered his speech, Britain had evacuated its forts from the Great Lakes following the Jay Treaty, and under the Treaty of Greenville, the Lenape and Shawnee started to move out of the region, moving west. We cannot separate the formation of the U.S. from a process of slavery and displacement, of genocide and cultural extermination, that erased the cosmovisions accumulated during thousands of years by African and Indigenous tribes. The replacement of their knowledge by “modern” worldviews divided nature and culture, male and female, tradition and industry. The baskets of Lorena Cruz are at the same time a continuation of the crafts of the Mixtec region in Oaxaca and an artifact sent to the future, carrying in its plastic life a code that will surpass human extinction. The synthetic and idea of synthetic lives designed to adapt to the uncertain forthcoming are at the core of Alden Jones’ project. In the form of a speculative practice of interactive design, Jones’ work situates us in another imaginary order, where subjects become objects, become attitudes, become enhanced personalities towards an accelerated market of services not yet provided by social networks. Business as a magic spell, in the dollar we trust.

These transformations in the flow of material life, seem to spill into the spirit of Kadar Brock’s pill bottles. Now refilled with ephemera, they are made tools of an unknown ritual—crafted to intervene in the psychospiritual vibrancy of bodies in pain. They appear as secret time capsules that contain the longing for a pre-pandemic world and a promise for healing. Brock’s interest in homeopathy brings us again to 1796, when the German doctor Samuel Hahnemann published an essay describing the power of drugs whose effects in healthy bodies were similar to those of the illnesses they cured. Hahnemann (who has a statue dedicated to him in Washington D.C.) believed that his science made previous healing methods obsolete and opened the doors to a different understanding of medicine. The homeopathic principle of “like cures like” could be interpreted as a precursor understanding on how vaccination works, roughly speaking “virus cures virus”.

Coinciding in time, floriography developed to associate flowers with symbolic meanings—an interest that would expand throughout the 19th Century, becoming a favorite thematic for romantics and cryptologists. The secret can be in plain daylight and yet be invisible to the eyes. Karen Azoulay expands this practice with a card deck that includes five combinatory orders, including hand-tricks, a poem generator, and tarot-esque divination games. Following this path, where history meets nature, we encounter Lee Hunter’s ceramic spikes, which serve as markers of portals for trans-dimensional travelling. Part of a larger project that speculates with a future yet to come, Hunter gathers objects and images, acting as an archivist of a world that mourns ecological destruction and experiences deep alterations in the live compositions of earthlings.

Although the future has collapsed in this present, we are at a turning point, where imagining the future order cannot be made with the tools of the present. The political theorist and filmmaker Ariella Aïsha Azoulay proposes to unlearn imperialism by “unlearning the processes of destruction that became possible: the knowledge, norms, procedures, and routines through which worlds are destroyed in order for people to become citizens of a differentially ruled body politic.” Unlearn to dismantle the divisions, and false neutralities that have been perpetuated by institutions, questioning universal concepts, principally contained in the notion of progress. Unlearn to go back to the past, questioning the inherited violence and imagine other forms of being together.

In 1796, Washington’s speech warned Americans to be vigilant against the usurpation of power, manipulations of the constitution, foreign interference, and social division. Although he was entangled in a cycle of violence that should be questioned, his words resonate in our present, in this pandemic, in this election year. Democracy cures democracy: get rid of the electoral college and vote.

-Xavier Acarín Wieland

Trust Fall

205 Hudson Gallery online viewing room, New York, NY, 2020

Local Flags

My Apartment, Brooklyn, NY, Rotating exhibits April-August 2020

image credit: Ricardo Contreras

Second Semester Show

205 Hudson Gallery, New York, NY, 2020

For Which it Stands

commissioned site specific work, Old Stone House, Brooklyn, NY, 2018

Obstructed Views

Scott Charmin Gallery, Houston, TX, 2016

image credit: Zach Krall